Reviews: Nanya Jhingran on Choi Seungja’s Phone Bells Keep Ringing For Me

Yes, phone bells rang endlessly for me,

and I didn’t want to avoid the call.

Even if I sank into the pit,

I wanted to touch

my fate.

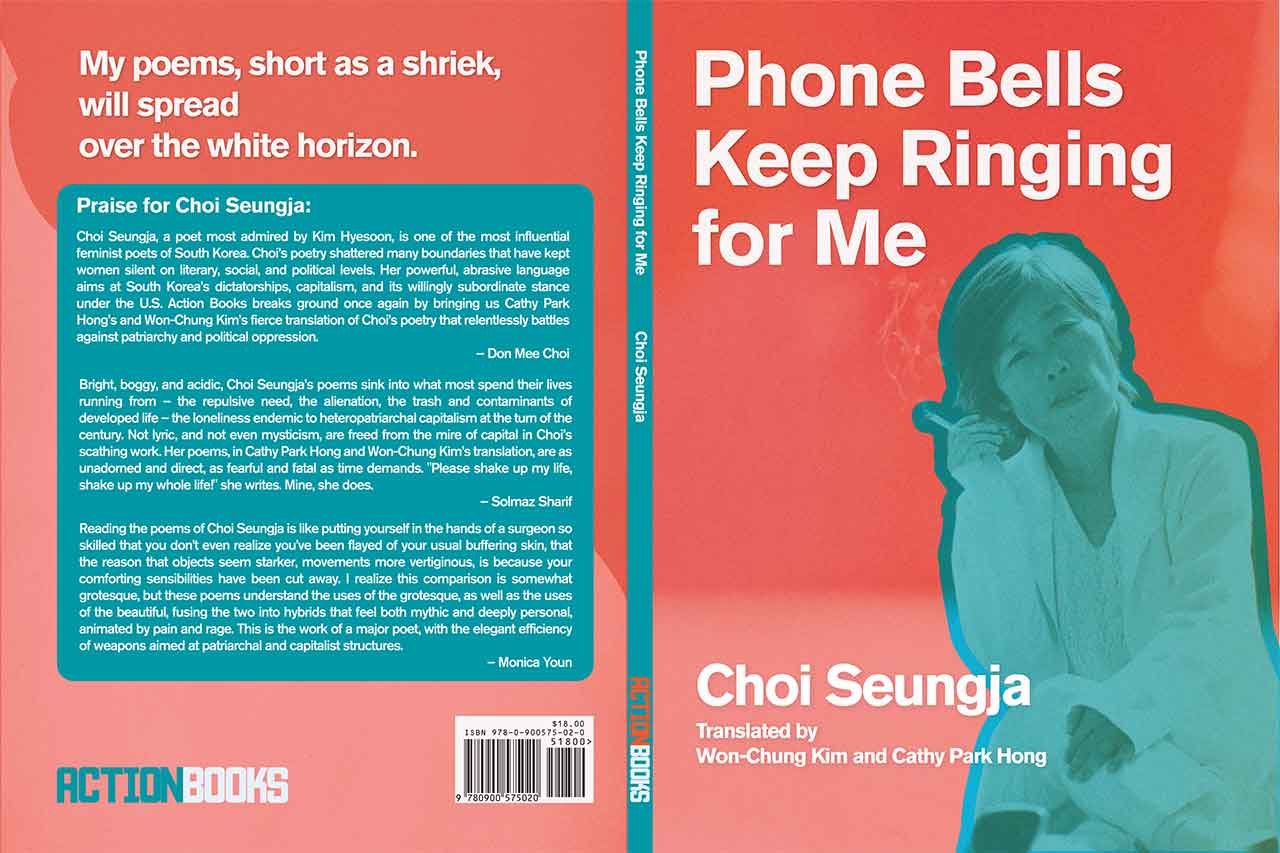

Choi Seungja, translated by Won-Chun Kim and Cathy Park Hong, edited by Joyelle McSweeney, Phone Bells Keep Ringing For Me. Action Books, October 2020, 104 pages, $18

By Nanya Jhingran

In one of the fragments in “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Walter Benjamin so describes a figure he calls “the angel of history”:

This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them.

Benjamin’s angel of history, now a staple of cultural studies syllabi, is a vehicle whose tenor is a kind of critical attentiveness towards the past that arrests linear, progressive time and recognizes that the archive of history continues to unfold as unabated catastrophe for all those who continue to be made fodder for capitalist and imperial development. Attending to the ravages of time, Benjamin’s angel is pulled by a redressive, melancholic attachment to the mounting tragedy of history. The poems in Korean feminist poet Choi Seungja’s Phone Bells Keep Ringing for Me, collected and translated by Won-Chung Kim and Cathy Park Hong, are written from a different sort of intimacy with ordinary life swallowed and spat out by the routinized violence of heteropatriarchal, imperial modernity. These poems reflect an experience of the late 20th century in South Korea: one marred by the ruptures of the Korean War and subsequent decades of authoritarian rule, a time which witnesses the massive and rapid growth of capitalist industries as well as brutal political and social repression and disenfranchisement.

No stranger to time’s false promises, the speaker in these poems does not keep the angel’s distance from the experience of the world — hers is a voice sounding out from within the debris, attempting to language that which may no longer be redeemable, or interested in redemption. Reading these poems, I am struck by Choi’s relentless and acute attention to how the everyday becomes shot through with material effluents when living in a postwar national economy driven by industrial manufacturing. In “Thirty Years Old,” the speaker finds parts of herself turning to spent industrial by-products as she ages,

Death’s traffic light blinks red

in my two eye sockets

my blood is jelly, my fingernails sawdust,

and my hair wire.

These poems ring out with an awareness of the mutilations dealt by the grating pace and growing waste of global capitalism upon one’s subjectivity and understanding of their own livingness. Across her poems, we can read an enduring curiosity towards what it could mean to be human without the false promises of future-as-progress, to sit within the “I,” in this aftermath, this abject relational rupture, this militarized-patriarchal silencing.

“Already I was nothing:,” begins the first poem of the collection, titled “Already I”:

Already I was nothing:

mold formed on stale bread,

trail of piss stains on the wall,

a maggot-covered corpse

a thousand years old.

Who is this I marooned onto itself, more waste than human, an effulgent trace of death and decay? Choi’s speaker languages the self as something that grows on, and is thus intimate with, that which pollutes, stains, and signals a state of neglect and decomposition. It is from the voice of these marks of decay, that Choi’s speaker announces her sense of affiliation with that which has been rendered abject by both time and society. Unmappable in the idiom of the hero or the savior, this is a speaker who instead finds in their own abjection an index of history’s many violations by fixing the gaze on what everyone turns away from, for fear or revulsion.

Far from nihilism, Choi’s turn towards the negative, the repressed, is to me a feminist turn: it is a refusal of vitality; of the emotional, physical, and material demands placed upon women which relegate them to the domestic, police them with discourses of virtue and duty, and thus simultaneously occlude and extract from them the constant labors of social reproduction. In the poem, “On Woman,” women become hollowed & hallowed by the machinery of care and regeneration housed within their body, a “ruined shrine and rigid dead sea” through which “everything has to pass […] in order to be born again and to die again.” These poems are cut with the precise knife of an effort to come into relation with one’s own slow destruction. In “For Y,” anger and revenge form the poetics of mourning a break-up and/as a lost future,

While dying, I saw my baby and me

Floating endlessly down the city ditch,

Down the city ditch and into the womb

Of bygone days.

These are also not, then, poems that solicit laid-back identification from the reader. They language the experiential despair and loneliness of existing within a world firmly within the ever-tightening grasp of capitalism, empire, and patriarchy. Choi’s writing does not offer the reader an aesthetic treatment of agony, nor a reading experience that goes unmarred by the pain that drives these poems. Lonely as they are, these poems are neither timid nor acquiescent. Instead, they ring out with decision, refusal, and threat. With exacting intention, these poems transform even the most familiar platitudes into premonitions of something more sinister. In her poem “Toward You,” what is initially a promise of intimacy, by the end of the poem threatens to contaminate:

Like flowing water,

I will come to you.

Like alcohol dissolving in water,

like nicotine congealing in alcohol,

like caffeine coating nicotine,

I will come to you.

Like syphilis germs flowing through veins,

like death gripping life.

Cynical about whether love can truly ameliorate or even suspend the drudgery of everyday existence, these poems exist in tension with the “you” they address themselves to. The idiom of desire swiftly reveals itself to hold within it great potential for violence. In the poem “To You,” again the love poem slips into a sinister threat:

The heart flows more easily than the wind.

Touching the tip of your branch,

I wish I could slip

into your heart

to become the eye

of a never-ending storm. (19)

Refusing the mirage of stability peddled by heteropatriarchal romance, Choi’s poems refuse the lover (“Go away, love or lover./To love is not to die for you.”) and turn instead to court Death itself, to language the experience of living as an effort to become familiar with Death. In later sections of the poetry collection, Choi’s speaker admits a sense of ease and acceptance towards what lies beyond one’s death. Speaking fondly in “Having No Way,” she says,

All things are endurable.

My cells seem to be getting old.

Though I am poor,

this room is cozy.

This running waterway is friendly,

the funeral of water is streaming away.

Please forgive me,

since the easiest me to dream of

is me in the grave.

By turning away from the familiar, scripted promises of the “good life,” these poems transform the inevitable and irreversible fact of death into a portal of possibility — something worth living for. I was struck time and time again in reading this book, of the deep vulnerability the poet must risk in their effort to language that which is obscured, unnameable, or otherwise elusive because it is challenging. Choi reminds the reader that this risk is also an offering — in “Poetry, or Charting a Way,” she says,

Yes, poetry is charting a way.

I have to chart a way

so I might cross ways with others.

I was grateful to have crossed paths with these poems in the Winter of 2020, for Phone Bells Keep Ringing for Me gave me language for how one can come into relation with death and see in it a complicated presence, in a year stilled by ungrievable, uncountable losses. “Limitation leads to a cliff,” Choi’s speaker states in “The End of a Century” — I think about the power in how her poems leap off this moment — this cliff.

About Nanya Jhingran

Nanya Jhingran (she/her) grew up in Lucknow, India and now lives and writes on the unceded lands of the Coast Salish peoples in Seattle, WA. She is a PhD Candidate in Literature and Culture and an MFA Candidate in Poetry at the UW. When she is not writing, reading, cooking for her friends, or walking around the city, she can be found playing with her cat Masala. Her poems and other writing have been published in The Boiler and Kajal Magazine and are forthcoming in New Limestone Review, Poetry Northwest, Snail Trail Press, and Honey Literary, among others.

About Choi Seungja

Choi Seungja was born in 1952 in South Korea, and emerged as a poet in the 80s, during a turbulent time marked by authoritarianism and widespread democracy movements. Her books include Love in this Age (1981), A Happy Diary (1984), The House of Memory (1989), My Grave is Green (1993), and Lovers (1999), Alone and Away (2010), Written on the Water (2011), and Empty Like an Empty Boat (2016). Since 2001, mental illness kept her in and out of hospitals. A community of poets and presses, led by the renowned poet Kim Hyesoon, came to Choi’s aid to help lift her out of poverty and enable her to continue to write.