Reviews: Identity as the Fractured Thing: Gustavo Barahona-López on Alan Chazaro’s Piñata Theory

by Gustavo Barahona-López

Piñata Theory by Alan Chazaro

Black Lawrence Press, 2020

Pages: 95. Paperback, $16.95

In Piñata Theory, winner of the 2018 Black Lawrence Press Hudson Prize, Alan Chazaro resists any monolithic characterization of who he is: a Mexican American millennial navigating the United States and Mexico but always in tune with the beat of the San Francisco Bay Area. In his debut full-length poetry collection, Alan Chazaro encapsulates the Mexican American experience growing up in the Bay Area through the incantation of specificity: using his speaker’s hyper-localized subject position to tackle many of humanity’s existential questions. It is in the specificity that he not only undermines popular representations of Mexican American people, but simultaneously offers his readers a multitude of avenues for connection. Contending with the many physical and psychological borders that the children of Mexican immigrants navigate, Chazaro employs the conceit of the piñata to represent how their identity is necessarily fractured. Personally, as a fellow pocho from the Bay Area, the points of deviation in our experiences bring as much joy as the moments my life and that of Chazaro’s speaker harmonize.

The poems in this collection are small rebellions against simple characterizations of what it is to be a pocho. Chazaro’s poem, “Broken Sestina as Soundscape” for instance reveals the speaker’s struggle over identity where the battlegrounds are soundscapes or their absence. The poem goes against many stereotypes about what it is like to be raised by Mexican immigrant parents. Chazaro’s speaker states:

How the room never danced because Pa never played

Juan Gabriel or other Mexican vocalists

in our house. After crossing the border,

he must’ve ditched a suitcase of himself at U.S. Customs. [16]

Here there are no rancheras and Vicente Fernandez wails. The father is desperately trying to show that he belongs in the United States. Further, the father loves his middle-class neighborhood and has a dream of “assimilating to cul-de-sac neighbors”. The speaker forgets about Spanish until a visit to Mexico. Mexicanness is compartmentalized by borders within the bodies of the father and the son. However, the son acculturates in his own way having previously “neglected the border’s//motherhood.” In place of Juan Gabriel he listens to Tupac and E-40. He creates his own form of belonging disparate from his father’s fantasies and views the world through a “mezcla of eyes” [17]. But all those sounds and influences continue to vibrate within the speaker since he has, “something new in my stereo always playing.” Just like the eclectic mix of musical influences that Chazaro references throughout his book, identity, this collection argues, is a playlist that can never be rendered down to an immutable essence.

Chazaro’s collection is an unabashedly generational work, which highlights the preoccupations of Mexican American millennials. When I read the title, “A Millennial Walks into a Bar and Says:” I imagine the poet sitting in a bar in the Mission District, sipping an IPA and nodding to the beat of Kendrick Lamar’s “DNA”. This poem is Chazaro at his disarming best. The speaker begins by referencing an unnamed Disney movie “because why/shouldn’t we?” [11] Chazaro’s speaker goes on to weave between history lessons and pop culture references. The poem is punctuated by profound questions that stop the reader in their tracks. Chazaro’s speaker contemplates: “We are byproducts of earthquakes. And English // is commonly spoken everywhere. Does anyone care / it started with rape?” [12] In this quote Chazaro reminds us of the violence of colonialism and the reverberations that other such ‘earthquakes’ continue to have upon our world. Later, the speaker emphasizes the role of youth in terms of bringing about change by invoking his students and “teenagers/[who] built cultures from wax while DJing inside broke // down project buildings” [12] in the South Bronx. The speaker takes the idea of social change a step further when he offers the reader the image of Bay Area poets Tongo Eisen-Martin and MK Chavez “hurling poems / at the heads of protestors in our streets while something burns” [13]. Part stream-of-consciousness monologue, part manifesto, “A Millennial Walks into a Bar and Says:” brings into focus the role that Chazaro’s generation plays in trying to remedy the world’s historical and contemporary issues.

The fracturing of Mexican American identity is perhaps captured best by the title poem, “Piñata Theory”. Much like the disparate socio-cultural factors that compose a person’s sense of self, the poem is divided into 5 disparate sections each exploring a different aspect of the piñata’s violent unraveling. The piñata is a symbol recognized as quintessentially Mexican in the U.S. mainstream. However, Chazaro subverts this image and instead uses it to critique the treatment of people of Mexican decent. The poem begins with the speaker being twirled and blinded in preparation for smashing his colorful prey. He then calls on us to, “Consider the violence / of living. How breath can be / fractured and displaced / while walking.” In a moment of stanza break alchemy, Chazaro’s speaker becomes the piñata declaring: “If I am a piñata then hang / Me with strings of coriander / And rainbow dust” [34] Then comes the ‘break’ whether it be the cracking of bones, severed papier-mâché appendages, or separation from home by borders. The speaker confesses to the reader “…I am / spilling myself and you are reaching to gather / whatever part of me is unbroken.” It is in the gathering of broken selves that the speaker offers the reader meaning. Chazaro’s speaker is tired of the threatened and actualized violence of institutional racism that devalues the lives of people of Mexican descent in the United States. Finally, the poem ends by highlighting the speaker’s expectation of suffering violence. The speaker states:

our breakage a celebration. / The truth?

We were made for beatdowns. [35]

While the communal ‘we’ are ‘made for beatdowns’ there is also a note of defiance and resilience in Chazaro’s words, no beating can ever truly destroy the pueblo. His poem demonstrates the tensions of belonging in the U.S. for people marginalized from power and the violence that comes with that precarity.

Piñata Theory reveals identity to be a series of softly glued assemblages, formed to be broken and made anew. He delves into the complexities of selfhood for one person and how they are influenced by immigration status, class, and gender identity. Chazaro’s speaker is constantly shaping and reshaping the contours of his being because “Someone built this bridge between [him]. They carved // hyphens from the air for [him] to cross.” [12/13] As someone who grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area, I love this book because it is an ode to those smoke-filled nights on stoops or Safeway parking lots. Because it makes those teenage escapades worthy of being elevated to art. This book made my life, my breaking, my joy something other than a spectacle for the white gaze. Chazaro’s poetry calls me back home.

About Gustavo Barahona-López

Gustavo Barahona-López is a poet and educator from Richmond, California. In his writing, Barahona-López draws from his experience growing as the son of Mexican immigrants. His micro-chapbook Where Will the Children Play? is part of the Ghost City Press 2020 Summer Series. A member of the Writer’s Grotto and VONA alum, Barahona-López’s work can be found or is forthcoming in Iron Horse Literary Review, Puerto del Sol, The Acentos Review, Apogee Journal, Hayden’s Ferry Review, among other publications. Twitter @TruthSinVerdad.

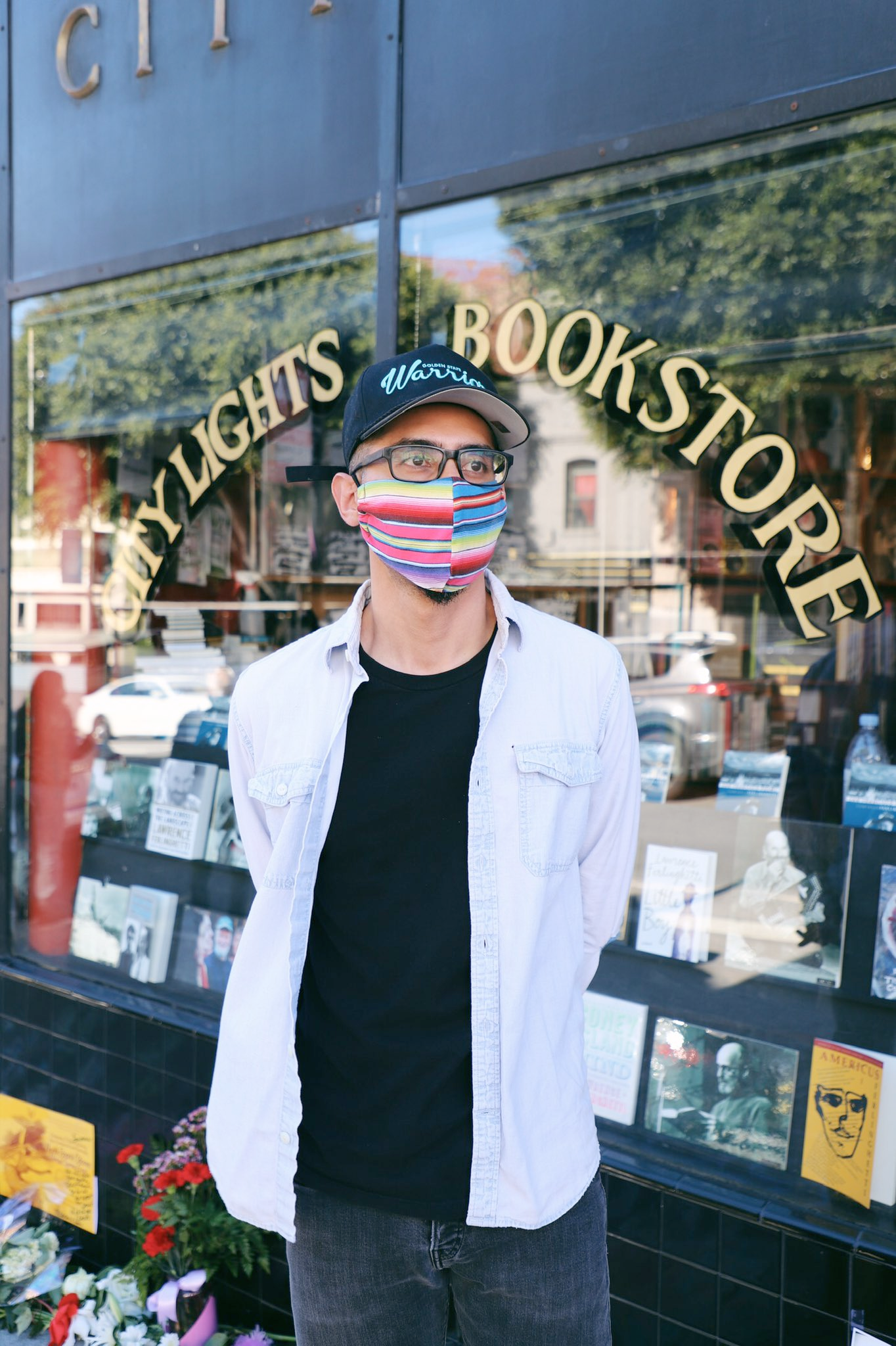

About Alan Chazaro

Alan Chazaro is the author of This Is Not a Frank Ocean Cover Album (Black Lawrence Press, 2019) and Piñata Theory (Black Lawrence Press, 2020). He is a graduate of June Jordan’s Poetry for the People program at UC Berkeley, a former Lawrence Ferlinghetti Fellow at the University of San Francisco, and co-founding editor of HeadFake, an online basketball zine. Catch him currently exploring the world of NBA Top Shot on Twitter @alan_chazaro.